They framed the debate around the question of whether federal funds should go to students as grants, as the Senate preferred, or as loans. Meeting in Montgomery, they devised a strategy for getting the NDEA enacted. Knowing that opponents in the House remained resistant, Senator Hill conferred with another Alabama Democrat, Representative Carl Elliott, who chaired the House subcommittee on education. There had been strong resistance to federal aid to education, but as public opinion demanded government action in the wake of Sputnik, the Senate once again moved ahead with its education bill.

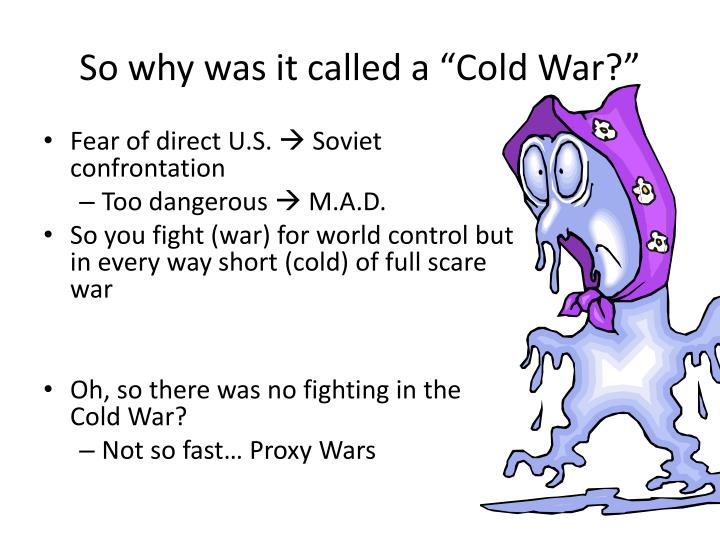

Senator Hill-a former Democratic whip and a savvy legislative tactician-seized upon on the idea, which led to the National Defense Education Act. Perhaps if they called the education bill a defense bill they might get it enacted. On the day Sputnik first orbited the earth, the chief clerk of the Senate’s Education and Labor Committee, Stewart McClure, sent a memo to his chairman, Alabama Democrat Lister Hill, reminding him that during the last three Congresses the Senate had passed legislation for federal funding of education, but that all of those bills had died in the House. Sometimes, however, a shock to the system can open political opportunities. Suddenly the nation found itself lagging behind the Russians in the Space Race, and Americans worried that their educational system was not producing enough scientists and engineers. During the Cold War, Americans until that moment had felt protected by their technological superiority. On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union shocked the people of the United States by successfully launching the first earth-orbiting satellite, Sputnik.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)